This is an early piece of "Nil nisi bonum de mortuis" in

interpreting Louis's rôle in the charge. ('Bob', who may just

possibly be his nephew Robert Macfarlane, was clearly unaware of the

verbal altercation with Lucan, and of the strange circumstances of

his death.) However, the quotations from

Cavalry: Its History and Tactics

are interesting and worth considering in the light of what happened.

The biographical data is reasonably good, even if it mis-spells his

first name (everyone had trouble with it!) and knocks a year off his

age: he was actually in his thirty-seventh year. Re: his family, his

full brothers, Archibald and Edmond, had died of fevers in the West

Indies and India respectively, and all of his half-brothers had also

predeceased him.

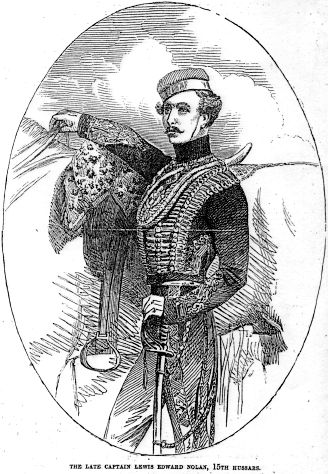

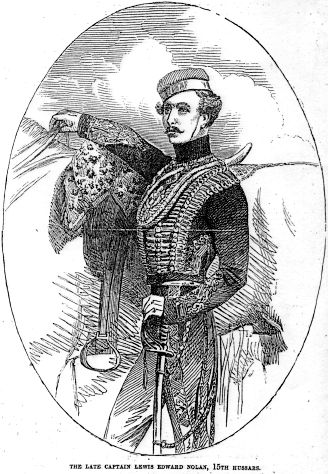

The original of the portrait is a naive watercolour in the

collection of the Light Dragoons.

THE ILLUSTRATED LONDON

NEWS

Nov. 25, 1854, p. 528

CAPTAIN LEWIS EDWARD

NOLAN,

LATE OF THE 15TH HUSSARS

THE

distinguished soldier, whose premature fate in connection with the

late heroic exploit of our Light Cavalry at Balaclava the Army and

the country have now to deplore, was a son of the late Major Nolan,

formerly of the 70th Regiment; who, after many years of arduous

service in various parts of the globe, retired from military life,

and became for some time resident at Milan, where he acted as

Vice-Consul, in the absence of the Consul-General, and was remarkable

for his hospitality. The best English and Continental society,

including military men of the highest rank, being constantly to be

met at Major Nolan's house, and Milan being a large garrison, it was

natural that, with such opportunities of association, his sons should

imbibe a predilection for the profession; and accordingly, at an

early age, Lewis (the subject of our Sketch) sought and obtained a

commission in the Austrian service, under the auspices of one of the

Imperial Grand Dukes, who was a friend of his father. In this

position he was generally esteemed for his amiable manners and strict

devotion to all the duties of military life; and it was here that he

first applied himself to the acquirement of that knowledge of the

menage and of Cavalry tactics, in which he became afterwards

so proficient - he being, even at this time, recognised as one of the

best horsemen in the division to which he was attached. After a short

service in Hungary, and on the Polish frontier, by the advice of his

friends, young Nolan sought a more distinguished career in the

British Army, and he was accordingly gazetted to an Ensigncy in the

4th Foot, on the 15th March, 1839; but in the month following he was

appointed to the 15th Hussars, then stationed in India; and after a

short stay at the Dépôt, joined his regiment at Madras,

where, his attractive talents having soon brought him under the

notice of Sir Henry Pottinger, then Governor of that Presidency, he

was appointed an extra Aide-de-Camp on his Excellency's Staff. In

addition to the knowledge which he already possessed of the French,

German, Italian, and Hungarian languages, Captain Nolan availed

himself of his residence in India to become master of several of the

native dialects; and he also entered actively into all the details of

the military system in the East. Apart from these engagements,

however, he found time for the sports of the field, and was several

times a successful competitor in some of the most severely-contested

steeplechases on the Madras turf. The 15th Hussars being ordered

home, and having previously obtained his troop, Captain Nolan

returned to England before the Regiment, on leave, and proceeded on a

tour in Russia; and having visited some of the most important

military posts in that empire, as well as in other parts of Northern

Europe, he returned to England, and published his justly popular book

upon the Organisation, Drill, and Manœuvres of Cavalry Corps,

which was reviewed at some length, with three Engravings, in the

ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS for Jan. 7, 1854. The work having attracted

the attention of the Horse Guards' authorities to its author, it is

already known that he received an appointment on the Staff of the

Army of the East; and, advantage being taken of his judgment in th

selection of horses, he was specially commissioned to make large

purchases on account of the Government, at Tunis, Syria, and

elsewhere - a duty which he performed to the entire satisfaction of

Lord Raglan. We are aware that in the first accounts of the

disastrous charge at Balaclava, blame was hastily attached to Captain

Nolan, who, it was alleged, had gone beyond the terms of an order

which he was instructed to deliver to Lord Lucan; his memory has,

however, we are glad to find, been subsequently vindicated from so

grave an imputation, and all who knew him best in the closest

relations of military life, and his punctilious character on all

points of duty, assert that he would have been the last man to be

guilty of the indiscretion attributed to him. In fact, the rash

movement in question was so opposed to his own published theory on

the subject, that he could never have willingly countenanced, much

less directed it, even under an excess of zeal. So far, indeed, from

this, in Captain Nolan's book, under General Rules, he says: -

THE

distinguished soldier, whose premature fate in connection with the

late heroic exploit of our Light Cavalry at Balaclava the Army and

the country have now to deplore, was a son of the late Major Nolan,

formerly of the 70th Regiment; who, after many years of arduous

service in various parts of the globe, retired from military life,

and became for some time resident at Milan, where he acted as

Vice-Consul, in the absence of the Consul-General, and was remarkable

for his hospitality. The best English and Continental society,

including military men of the highest rank, being constantly to be

met at Major Nolan's house, and Milan being a large garrison, it was

natural that, with such opportunities of association, his sons should

imbibe a predilection for the profession; and accordingly, at an

early age, Lewis (the subject of our Sketch) sought and obtained a

commission in the Austrian service, under the auspices of one of the

Imperial Grand Dukes, who was a friend of his father. In this

position he was generally esteemed for his amiable manners and strict

devotion to all the duties of military life; and it was here that he

first applied himself to the acquirement of that knowledge of the

menage and of Cavalry tactics, in which he became afterwards

so proficient - he being, even at this time, recognised as one of the

best horsemen in the division to which he was attached. After a short

service in Hungary, and on the Polish frontier, by the advice of his

friends, young Nolan sought a more distinguished career in the

British Army, and he was accordingly gazetted to an Ensigncy in the

4th Foot, on the 15th March, 1839; but in the month following he was

appointed to the 15th Hussars, then stationed in India; and after a

short stay at the Dépôt, joined his regiment at Madras,

where, his attractive talents having soon brought him under the

notice of Sir Henry Pottinger, then Governor of that Presidency, he

was appointed an extra Aide-de-Camp on his Excellency's Staff. In

addition to the knowledge which he already possessed of the French,

German, Italian, and Hungarian languages, Captain Nolan availed

himself of his residence in India to become master of several of the

native dialects; and he also entered actively into all the details of

the military system in the East. Apart from these engagements,

however, he found time for the sports of the field, and was several

times a successful competitor in some of the most severely-contested

steeplechases on the Madras turf. The 15th Hussars being ordered

home, and having previously obtained his troop, Captain Nolan

returned to England before the Regiment, on leave, and proceeded on a

tour in Russia; and having visited some of the most important

military posts in that empire, as well as in other parts of Northern

Europe, he returned to England, and published his justly popular book

upon the Organisation, Drill, and Manœuvres of Cavalry Corps,

which was reviewed at some length, with three Engravings, in the

ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS for Jan. 7, 1854. The work having attracted

the attention of the Horse Guards' authorities to its author, it is

already known that he received an appointment on the Staff of the

Army of the East; and, advantage being taken of his judgment in th

selection of horses, he was specially commissioned to make large

purchases on account of the Government, at Tunis, Syria, and

elsewhere - a duty which he performed to the entire satisfaction of

Lord Raglan. We are aware that in the first accounts of the

disastrous charge at Balaclava, blame was hastily attached to Captain

Nolan, who, it was alleged, had gone beyond the terms of an order

which he was instructed to deliver to Lord Lucan; his memory has,

however, we are glad to find, been subsequently vindicated from so

grave an imputation, and all who knew him best in the closest

relations of military life, and his punctilious character on all

points of duty, assert that he would have been the last man to be

guilty of the indiscretion attributed to him. In fact, the rash

movement in question was so opposed to his own published theory on

the subject, that he could never have willingly countenanced, much

less directed it, even under an excess of zeal. So far, indeed, from

this, in Captain Nolan's book, under General Rules, he says: -

Rule 3. Never attack without keeping part of your

strength in reserve.

9. Charges on a large scale should seldom be attempted against

masses of all arms, unless they have previously been shaken

by fire. 10. Always watch for and seize the right moment to

attack.

And, again, he says prophetically: -

The most difficult position a cavalry officer can be

placed in is in command of cavalry against cavalry; for the

slightest fault committed may be punished on the spot.

All these errors were made, however, under some horrible delusion.

The Light Cavalry galloped, open-eyed, into destruction as complete

as if they had fallen into an ambuscade. Who can doubt that if they

had had to charge any reasonable number of Russian infantry or

cavalry, clear of the batteries, that they would have ridden them

down? As it was, they sabred the artillerymen at their guns. Captain

Nolan was struck on the heart by one of the first shells, gave a loud

cry, and died instantly. His horse turned and galloped back with his

dead rider firm in his saddle.

At the time of his death he was in his thirty-sixth year, and had

shared in the battle of the Alma, as Aide-de-Camp to

Brigadier-General Airy, Deputy-Quartermaster-General. He leaves a

bereaved mother, a widow, who had already lost two sons in the

service, to mourn the early fall of the last, who was at once her

only pride and hope.

The accompanying Portrait is from a picture painted in India.

We subjoin an extract from a letter written by a young officer,

dated "Camp before Sebastopol, October 28": -

Poor Lewis Nolan has gone to his rest. In a cavalry

action three days ago he bore an order from Lord Raglan to Lord

Lucan to charge a battery of heavy field-pieces, and in the act of

delivering it, a piece of shell struck him on the left breast, and

passed through his body. Death, by the mercy of Heaven, was

instantaneous. Poor Lewis! he was a gallant soul. The day before

his death, I am glad to think, I met him, and he said, "Well, Bob,

is not this fun? I think it is the most glorious life a man could

lead." Few men of his years promised to be such an ornament to his

profession. I am sorry to say, now that he is gone, some people

here say that in the heat of the moment, poor Lewis gave Lord

Lucan a wrong order. Such is not the case. The order was a written

one, and therefore the mistake was not on his side.

THE

distinguished soldier, whose premature fate in connection with the

late heroic exploit of our Light Cavalry at Balaclava the Army and

the country have now to deplore, was a son of the late Major Nolan,

formerly of the 70th Regiment; who, after many years of arduous

service in various parts of the globe, retired from military life,

and became for some time resident at Milan, where he acted as

Vice-Consul, in the absence of the Consul-General, and was remarkable

for his hospitality. The best English and Continental society,

including military men of the highest rank, being constantly to be

met at Major Nolan's house, and Milan being a large garrison, it was

natural that, with such opportunities of association, his sons should

imbibe a predilection for the profession; and accordingly, at an

early age, Lewis (the subject of our Sketch) sought and obtained a

commission in the Austrian service, under the auspices of one of the

Imperial Grand Dukes, who was a friend of his father. In this

position he was generally esteemed for his amiable manners and strict

devotion to all the duties of military life; and it was here that he

first applied himself to the acquirement of that knowledge of the

menage and of Cavalry tactics, in which he became afterwards

so proficient - he being, even at this time, recognised as one of the

best horsemen in the division to which he was attached. After a short

service in Hungary, and on the Polish frontier, by the advice of his

friends, young Nolan sought a more distinguished career in the

British Army, and he was accordingly gazetted to an Ensigncy in the

4th Foot, on the 15th March, 1839; but in the month following he was

appointed to the 15th Hussars, then stationed in India; and after a

short stay at the Dépôt, joined his regiment at Madras,

where, his attractive talents having soon brought him under the

notice of Sir Henry Pottinger, then Governor of that Presidency, he

was appointed an extra Aide-de-Camp on his Excellency's Staff. In

addition to the knowledge which he already possessed of the French,

German, Italian, and Hungarian languages, Captain Nolan availed

himself of his residence in India to become master of several of the

native dialects; and he also entered actively into all the details of

the military system in the East. Apart from these engagements,

however, he found time for the sports of the field, and was several

times a successful competitor in some of the most severely-contested

steeplechases on the Madras turf. The 15th Hussars being ordered

home, and having previously obtained his troop, Captain Nolan

returned to England before the Regiment, on leave, and proceeded on a

tour in Russia; and having visited some of the most important

military posts in that empire, as well as in other parts of Northern

Europe, he returned to England, and published his justly popular book

upon the Organisation, Drill, and Manœuvres of Cavalry Corps,

which was reviewed at some length, with three Engravings, in the

ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS for Jan. 7, 1854. The work having attracted

the attention of the Horse Guards' authorities to its author, it is

already known that he received an appointment on the Staff of the

Army of the East; and, advantage being taken of his judgment in th

selection of horses, he was specially commissioned to make large

purchases on account of the Government, at Tunis, Syria, and

elsewhere - a duty which he performed to the entire satisfaction of

Lord Raglan. We are aware that in the first accounts of the

disastrous charge at Balaclava, blame was hastily attached to Captain

Nolan, who, it was alleged, had gone beyond the terms of an order

which he was instructed to deliver to Lord Lucan; his memory has,

however, we are glad to find, been subsequently vindicated from so

grave an imputation, and all who knew him best in the closest

relations of military life, and his punctilious character on all

points of duty, assert that he would have been the last man to be

guilty of the indiscretion attributed to him. In fact, the rash

movement in question was so opposed to his own published theory on

the subject, that he could never have willingly countenanced, much

less directed it, even under an excess of zeal. So far, indeed, from

this, in Captain Nolan's book, under General Rules, he says: -

THE

distinguished soldier, whose premature fate in connection with the

late heroic exploit of our Light Cavalry at Balaclava the Army and

the country have now to deplore, was a son of the late Major Nolan,

formerly of the 70th Regiment; who, after many years of arduous

service in various parts of the globe, retired from military life,

and became for some time resident at Milan, where he acted as

Vice-Consul, in the absence of the Consul-General, and was remarkable

for his hospitality. The best English and Continental society,

including military men of the highest rank, being constantly to be

met at Major Nolan's house, and Milan being a large garrison, it was

natural that, with such opportunities of association, his sons should

imbibe a predilection for the profession; and accordingly, at an

early age, Lewis (the subject of our Sketch) sought and obtained a

commission in the Austrian service, under the auspices of one of the

Imperial Grand Dukes, who was a friend of his father. In this

position he was generally esteemed for his amiable manners and strict

devotion to all the duties of military life; and it was here that he

first applied himself to the acquirement of that knowledge of the

menage and of Cavalry tactics, in which he became afterwards

so proficient - he being, even at this time, recognised as one of the

best horsemen in the division to which he was attached. After a short

service in Hungary, and on the Polish frontier, by the advice of his

friends, young Nolan sought a more distinguished career in the

British Army, and he was accordingly gazetted to an Ensigncy in the

4th Foot, on the 15th March, 1839; but in the month following he was

appointed to the 15th Hussars, then stationed in India; and after a

short stay at the Dépôt, joined his regiment at Madras,

where, his attractive talents having soon brought him under the

notice of Sir Henry Pottinger, then Governor of that Presidency, he

was appointed an extra Aide-de-Camp on his Excellency's Staff. In

addition to the knowledge which he already possessed of the French,

German, Italian, and Hungarian languages, Captain Nolan availed

himself of his residence in India to become master of several of the

native dialects; and he also entered actively into all the details of

the military system in the East. Apart from these engagements,

however, he found time for the sports of the field, and was several

times a successful competitor in some of the most severely-contested

steeplechases on the Madras turf. The 15th Hussars being ordered

home, and having previously obtained his troop, Captain Nolan

returned to England before the Regiment, on leave, and proceeded on a

tour in Russia; and having visited some of the most important

military posts in that empire, as well as in other parts of Northern

Europe, he returned to England, and published his justly popular book

upon the Organisation, Drill, and Manœuvres of Cavalry Corps,

which was reviewed at some length, with three Engravings, in the

ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS for Jan. 7, 1854. The work having attracted

the attention of the Horse Guards' authorities to its author, it is

already known that he received an appointment on the Staff of the

Army of the East; and, advantage being taken of his judgment in th

selection of horses, he was specially commissioned to make large

purchases on account of the Government, at Tunis, Syria, and

elsewhere - a duty which he performed to the entire satisfaction of

Lord Raglan. We are aware that in the first accounts of the

disastrous charge at Balaclava, blame was hastily attached to Captain

Nolan, who, it was alleged, had gone beyond the terms of an order

which he was instructed to deliver to Lord Lucan; his memory has,

however, we are glad to find, been subsequently vindicated from so

grave an imputation, and all who knew him best in the closest

relations of military life, and his punctilious character on all

points of duty, assert that he would have been the last man to be

guilty of the indiscretion attributed to him. In fact, the rash

movement in question was so opposed to his own published theory on

the subject, that he could never have willingly countenanced, much

less directed it, even under an excess of zeal. So far, indeed, from

this, in Captain Nolan's book, under General Rules, he says: -