OF

CAVALRY REMOUNT HORSES.

INTRODUCTION.

THIS new system of Equitation was invented by Monsieur Baucher; and, for any thing that is good in this book, the credit is due to him.

I had at first intended translating his work from the French; but experience shewed me that certain modifications were necessary to adapt it to the use of our cavalry. I therefore determined on publishing the lessons as I myself had carried them out with many horses of different breeds and countries, adding what my experience* suggested; and as I found that those lessons succeeded with all, without exception, I can safely assert, that any horseman of common capacity, following them out in the same way, will break in his horse perfectly in about two months' time.

The system rests on a few simple principles, shewing how to attack each point in succession, and thus enabling the rider at last to reduce his horse to perfect obedience. The horseman, in the success he daily obtains, finds a constant incitement to continue his exertions; the only thing to guard against is undue haste, and the wish to obtain too much at once.

By this plan the time of training is shortened so much, that one's interest in the daily progress of the horse never flags; the man works with good will, and many a horse is thus preserved from the effects of bad temper in the rider.

It saves many a young horse from the ruin occasioned by the use of the longe and other substitutes for skill in the riding school.•

The progress made is so gradual, that it never rouses the horse's temper.

It improves the horse's paces, makes him light in hand, and obedient, adds greatly to the appearance and efficiency of each individual horseman, from the way the horses learn to carry themselves, and the confidence the man naturally has when riding an animal he feels to be completely under his control.

In case of emergency, cavalry could, by this system, prepare any number of young horses for the field in an incredibly short space of time; for though about two months are required to complete the lessons, the horses could be made available for service much sooner.

All other books on equitation speak in general terms, but never point out where to begin, how to go on, or when to leave off.

According to the old school, when you had arrived at the "height" of perfection, your horse was constantly sitting down on his haunches - "a great object to have gained after a couple of years hard and dull work!"

In the old school much was written about equilibrium; the horse's hind legs were drawn under him and rooted to the ground, whilst his fore legs were always scrambling in the air;

and those horses that were perfect had acquired a way of going up and down, much resembling the motion of a hobbyhorse; too much weight was thrown on the haunches, and a horse could neither raise his hind leg to step back when required, nor could he dash forward with any speed whilst made to throw his weight backwards.

The horse, again, whose weight was thrown forward was still worse and more dangerous, for the weight of the rider often brought him to the ground; and at all times the bearing on the hand was so great as to require the strength of both arms to resist it - thus, the horseman, having no power over his horse, became in a great measure useless as a soldier.

The true equilibrium, which is neither on the haunches, nor on the forehand, but between the two, Mons. Baucher alone has shewn us how to obtain, by carefully gathering up and absorbing one by one all the resources of the horse, and uniting them in one common centre, where they are held at the disposal, at the sovereign will and pleasure, of the horseman.

*The author served for some time in the Hungarian Hussars, and was a pupil of Colonel Haas, the instructor of the Austrian Cavalry.

•The longe is useful, indeed often necessary, with refractory horses; but the use of it should be made the exception, and not the rule.

1. - Introductory Remarks, on the Health and Condition of the Horses - On Punishments, Obedience, Resistance, Weakness - Vice, Plunging, Rearing - How to fall clear of a Horse when he throws himself backwards - Starting - If a Horse turns round, how to proceed.

THE health and condition of the horses should be carefully considered, and great care be taken not to over-fatigue them by too violent exertion. Remember to husband their resources, and never overwork them; bc as careful of their tempers as of their legs, for a restive horse is of little use in war. Punishment should never be inflicted on a young horse, except for decided restiveness and downright vice. Even in that case, your object only being to oblige him to go forward, you will, the moment he moves on, treat him kindly.

When a horse resists, before a remedy or correction is thought of, examine minutely all the tackle about him. For want of this necessary precaution, the poor animal is often used ill without reason, and being forced into despair, is in a manner obliged to act accordingly, be his temper and inclination ever so good.

Horses are by degrees made obedient through the hope of recompense, as well as the fear of punishment. To use these two incentives with judgment is a very difficult matter, requiring much thought, much practice, and not only a good head, but a good temper; more force, and want of skill and coolness, tend to confirm vice and restiveness. Resistance in horses is often a mark of strength and vigour, and proceeds from high spirits; but punishment would turn it into vice.

Weakness frequently drives horses into being vicious when anything wherein strength is necessary is required of them. Great care should be taken to distinguish from which of these causes the opposition arises.

It is impossible in general to be too circumspect in lessons of all kinds, for horses find out many ways and means of opposing what you demand of them. Many will imperceptibly gain a little every day on their rider; he must, however, always treat them kindly, at the same time, shewing that he does not fear them, and will be master.

Plunging is very common amongst restive horses If they continue to do it in one place, or backing, they must be, by the rider's legs and whip firmly applied, obliged to go forward; but, if they do it flying forwards, keep them back, and ride them gently, and very slow, for a good time together. Of all bad tempers in horses, that which is occasioned by harsh treatment and ignorant riders is the worst.

Rearing is a bad vice, and, in weak horses especially, a dangerous one; whilst the horse is up, the rider must yield the hand, and at the time he is coming down again, he must vigorously determine him forwards; if this be done at any other time but when the horse is coming down, it may add a spring to his rearing, and make him come over. If this fails, you must make the horse move on by getting some one on foot to strike him behind with a whip. With a good hand on them, horses seldom persist in this vice, for they are themselves much afraid of falling backwards. When a horse rears, the man should put his right arm round the horse's neck, with the hand well up, and close under the horse's gullet; he should press his left shoulder forward, so as to bring his chest to the horse's near side; for if the horse falls back, he will then fall clear.

Starting often proceeds from a defect in the sight, which, therefore, must be carefully looked into. Whatever the horse is afraid of, bring him up to it gently, and if you make much of him every step he advances, he will go quite up to it by degrees, and soon grow familiar with all sorts of objects. Nothing but great gentleness can correct this fault; for, if you inflict punishment, the dread of the chastisement causes more starting than the fear of the object; if you let him go by the object without bringing him to it, you increase the fault, and encourage him in his fear. However, if a horse turns back, you must punish him for doing so, and that whilst his head is away from the object; then turn him, and ride him up quietly towards what he shied at, and make much of him as long as he moves on; never punish him with his head to the object, for if you do he is as badly off with his head one way as the other, whereas, when the horse finds out that he is only punished on turning back, he will soon give it up. If a horse takes you up against a wall and leans to it, turn his head to the wall, and not away from it.

WHEN Remount Horses join a regiment, they should be distributed amongst the old horses; they thus become accustomed to the sight of saddles and accoutrements, to the rattling of the swords, &c., &c., and the old horses on each side of them, taking no notice of all these things, inspire the young ones with confidence.

The Veterinary Surgeon first takes them in hand, and a dose of physic previous to their going into work is advisable; meanwhile, the men should handle them, and saddle them quietly, under the superintendence of a non-commissioned officer. They will thus be quietly preparing for their work in the school.

The first day they are led down to the riding school in saddles, with snaffle bridles, the Riding Master should inspect the saddles, see that the cruppers, breast plates, and girths, are rather loose, so as not to inconvenience the horses; he should then order the men to mount quietly, and at once file them at a walk round in a large circle, and whilst so doing, divide them into rides of twelve, fourteen, or sixteen each. He should pick out all the horses that are in poor condition, or weak, or very young, and make a ride of them, giving them less work than the others.

The Riding Master should allow no shouting, and no noise in the rides, and even the words of command should be cautiously given at first, so as not to startle or set off the young horses. When the rides are told off, they are filed to stables. If any of the homes are intractable, the men should dismount and lead them home; but all those that go quietly should go and come from school mounted, the files being at a horse's length interval and distance.

Plenty of running reins should be distributed; they are a great help to a man at first, in keeping the horse's head steady, and they never do harm; but they should always have some play, and a man must never be allowed to have a pull upon them.

If any of the horses will not allow the men to mount, put a cavesson on, stand in front of the horse, raise the line with the right hand, and play with it, speaking to the horse at the same time to engage his attention, whilst the man quietly mounts; no one else should be allowed near, as the more people round a horse the more alarmed he is, and the more difficult to manage. As soon as the man has mounted, turn your back to the horse, and walk on, leading him amongst the other horses, and round with them - he will soon follow their example. A few dismounted men are necessary to take hold and lead those horses that are unsteady when mounted, and if any one of them stands still, take care that the man trying to lead him on, does not pull at his bridle, and look him in the face, which will effectually prevent the animal from moving forward; make the man who leads the horse turn his back and go on, and, in ten cases out of twelve, the horse will follow.

In mounting young horses, place the left hand rather high up on the mane, and with the right take hold of the pommel, not the cantle of the saddle, you can thus always swing yourself on to the horse's back; whereas, if your right hand is on the cantle, and the horse springs forward, or turns round, in trying to pass the leg over the horse, you must let go your hold with the right hand, and thus you lose your balance, and are thrown off. By the other way, you hold on with both hands, the saddle is open to receive you, and you can swing yourself into it in spite of anything the animal may do to prevent you.

"THE object is through certain indications to make yourself understood and obeyed by the horse: and it is necessary that these indications shall be such, that the rider can employ them under all circumstances, and when making use of the sword."

Cavalry soldiers are ordered to turn their horses on the "inward rein," that is, with the right rein to the right, with the left rein to the left; but they turn them on the outward rein chiefly; this is too well known to require comment, for to invent the means of accomplishing this object with the inward rein, has long been a problem amongst the professors of horsemanship, various books having been written on the subject.

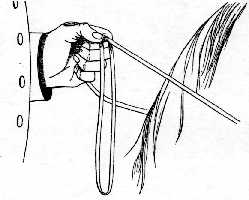

General Kress v. Kressenstein, an Austrian cavalry general proposed fastening the bit reins at a certain length, and dividing them with the whole hand, (vide fig.) to enable the man to feel

the right rein when turning to the right, the left rein when turning to the left; but this and other systems proposed, have more of disadvantage than advantage in them.

Let us select two cavalry services, the English and Austrian, and see what the instructions are for turning a horse to either hand.

In both services, the system is to turn the horse on the inward rein; to do this it is necessary to shorten that rein considerably.

"To turn to the Right." (English Cavalry Instructions.) "Turn the little finger of the left hand towards the right shoulder.""To turn to the Right." (Austrian Cavalry Instructions.) "Turn the little finger up towards the left shoulder."

"To turn to the Left." (English Cavalry Instructions.) "Turn the little finger of the left hand towards the left shoulder."

"To turn to the Left." (Austrian Cavalry Instructions.) "This is done by turning the little finger towards the right, the thumb falling forward."

Thus the artistic contortion of the bridle hand, which turns an English horse to the right, has exactly the contrary effect upon the Austrian, for it turns him to the left; and that turn of the bridle hand, which is to bring the English horse to the left, makes the imperial one turn to the right.

Now let any one divide the reins with the little finger, and see whether by following these instructions, it is possible on either system to shorten the inward rein to any extent, and whether in doing so, he does not feel the other rein also; thus it cannot be with the inward rein that the horse is turned, because you cannot shorten that rein sufficiently to turn the horse without pulling the other rein at the same time.

According to one of the above systems, the soldier, whilst turning to the right to meet his antagonist, is to turn his body one way and his hand another.

A dragoon uses one hand for the reins, the other for the sword, and the system requires that the bridle arm shall be a fixture, that the bridle hand shall only move from the wrist, and that this latter shall be rounded outwards: the whole position is constrained, almost painful. When a troop horse is bad tempered, or tired, he is not always inclined to obey the very slight indications given "from the wrist;" thus the first time the soldier gets into difficulties he is reduced to letting the horse have his own way, or he must use his bridle hand with a little more energy (than the system admits of) to bring the horse to obedience; still he attains his object with difficulty, because the animal has not yet learnt to understand the aids which necessity has driven the rider to invent for the occasion.

The horse, whilst breaking in on the snaffle, has always been turned on the inward rein, and when bitted, he is made to turn on the outward rein, without ever having been taught to do so!

The conclusions to be drawn from the above are: that as both English and Austrian Cavalry can turn their horses to the right or left, and by exactly the reverse contortions of the wrist, these said contortions can be of little consequence either way; by neither process can the inward rein be shortened without pulling the outward rein (particularly when strength is required). Thus, it is evident, it is not the inward rein which forces the horse into the new direction.

The fact is, the use of the outward rein is absolutely necessary; and not only the outward rein, but I go further, and say, that "no feeling of the rein is a right one, without the assistance of the other rein, and both the rider's legs;" for, in the first instance you work on the head and neck alone, and that imperfect whereas, in the latter, you work upon the whole horse at once. When a horse is ridden on the snaffle, he only feels the direct pull more or less strong of the rider's hand; with a bit in his mouth, the effect is different and more powerful, on account of the lever, which tightens the curb chain on the lower jaw of the horse, and forces him to yield with head and neck. The rider is connected with this lever by the reins, and acts upon the horse by the weight of his body, and the pressure of the legs, much as he does with the bit. If you put a bridle in the horse's mouth for the first time, mount him, and carry the bridle hand to the right, throwing the weight of the body to that side, the horse will turn to the right, though you may have felt the left rein more than the right one, and this because the tension of the reins which proceeded from a central point being suddenly changed to a point on the right, and the horse feeling all the weight inclining to that side, as you would step under a weight you were carrying, to prevent it from falling, so does the horse feel the necessity of following, till the equilibrium between himself and his load be re-established. How useless then are all those studied and difficult movements of the bridle hand, since, turn your little finger into whatever difficult position you like, if you bring it at the same time your bridle hand and body to the same side, to that side will the horse turn. Let us therefore profit by this natural inclination of the horse, and impress those aids upon him by education, which by instinct he already inclined to obey.

The life of the cavalry soldier must often depend upon his being able to turn his horse to either hand: it is therefore important that means should be placed at the man's disposal to enable him to attain his object, with some degree of certainty; the system should be; one which can be carried out by all men upon all horses; the aids should be natural and easy to the man, and intelligible to the animal; to this purpose I think that

The position and action of the bridle hand and arm should be as follows:

The upper arm perpendicular from the shoulder, the lower arm resting lightly on the hip for support.

Bridle hand opposite the centre, and about three inches from the body, with the knuckles towards the horse's head, thumb pointing across the body, and a little to the right front, the hand as low as the saddle will allow of, held naturally without constraint.

The wrist in a natural position, not rounded outwards, which deprives the hand of the action from front to rear, and makes the whole arms stiff.

The bit reins divided by the little finger, the snaffle reins brought through the full of the hand, the thumb upon the reins, but not pressed down upon them, to avoid giving stiffness to the hand.

In dividing the bit reins with the little finger, the right rein which passes over the finger is always a little longer than the other and requires to be shortened; if this is not attended to, the horse is ridden chiefly on the left rein, he is wrongly "placed" from the beginning, (his head being bent to the left,) and can never work well; for one of the great principles in Equitation is, when moving in a straight line to keep your horse's head straight, and when turning to either hand, to let the horse look the way he is going.

"To Turn to the Right." Carry your hand to the right with the knuckles up."To Turn to the Left." Carry the hand to the left, and bend it back slightly from the wrist, thumb pointing to the front, knuckles turned down.

"To Pull Up." Keep the hand low, the body back, and shorten the reins by drawing back the bridle arm.

In breaking in horses, teach them by the use of the inward rein to turn their heads into the new direction; at the same time always make them feel the pressure of the outward rein against the neck. Thus when the rider (with the reins in his left hand) carries his hand to the right, the right rein being the first felt, inclines the horse's head that way, and the pressure of the left rein against his neck, which unavoidably follows, induces the horse to turn to the right.

To the left, vice versâ.

When turning a young horse the first few times, put the right hand to the inward rein whenever he hesitates in turning, to shew him the way.

These aids are so simple and so marked, that the man can never make a mistake, nor can the horse misunderstand them; hand and body work together; they are sure to be resorted to on an emergency, because natural to the man, and therefore the best to adopt in practice.