Major

PATRICK FERGUSON,

71st Foot, Inspector of Militia

1744-80

The Scottish Enlightenment's Swashbuckling

Hero

(who gave

Whistle-World

its title...)

ON SALE

NOW!!!

|

PATRICK FERGUSON:

"A Man of Some

Genius"

M M Gilchrist

National Museums of Scotland, 2003,

£7.99

ISBN 1 901663 74 4

Available from the National Museums of Scotland and

the Royal Armouries

Orderable from good bookshops and on the net:

|

Biography

Biography

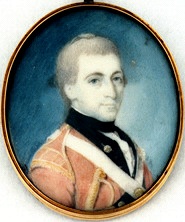

The 'Bulldog': thin, wiry, implausibly swashbuckling designer

of the Ferguson Breechloading Rifle. Gentle, cultured, a gallant

spirit with an elfin face and a witty sense of humour even in the

face of crippling disability, Pattie is perhaps the most endearing of

18C military heroes. He wrote verses, cracked jokes even about

unanaesthetised surgery, and left a charming legacy of letters and

legends in his wake.

(The portrait here is a miniature from life in a private

collection. He is dressed as an officer of the light infantry company

of the 70th Foot, with his hair in light infantry style - the braided

queue pinned to the top of his head.Unpowdered, it was brown - some

of it is in the back of the frame!)

His family

was at the heart of the Scottish Enlightenment - they knew the

Ramsays, Hume, Home, Smollett, Adam Ferguson, & c. They lived on

3 floors (another floor was their servants' quarters) of a 7-storey

tenement on the High Street, east of Roxburgh's Close, where our boy

was probably born on 24 May (OS)/4 June (NS) 1744.

Visit our Scottish

Tour to see some of the places associated with him and his

family in Edinburgh,

Fife

and Aberdeenshire!

(He also had the usual quota of embarrassing Jacobite relatives:

Uncle Sandy Murray who plotted with Charles Edward Stuart to abduct

or assassinate the entire royal family; it didn't work, as the "with

Charles Edward Stuart" bit tends to louse up anything! Then there was

cousin Margaret Johnstone, Lady Ogilvy, who escaped from Edinburgh

Castle in male drag...)

In 1756, when Pattie was 12, his father purchased an ensigncy for

him in his uncle Colonel James Murray's regiment, the 15th Foot, but

it was cancelled, since, with war brewing, he was too "young &

little" to be of service. In 1759, shortly after his fifteenth

birthday, Pattie was bought a Cornetcy in the Royal North British

Dragoons (Scots Greys). However, he did not join his regiment until

1761. For nearly two years he studied at the Royal Military Academy

in Woolwich, on the recommendation of Uncle Jamie (by then General

Murray - Wolfe's successor, and Military Governor of Quebec). There

he developed a lifelong interest in the design of fortifications,

under the tuition of the noted expert John Muller.

Pattie embarked for Germany with his regiment in spring 1761, to

serve in the Seven Years' War. His active service was cut short at

the turn of 1761-2 by a leg ailment, possibly TB, which kept him

bedridden in Osnabrück for six months. He returned home in

summer 1762, and spent a year convalescing in Edinburgh with his

parents, and at Pitfour (which he had never visited before) with his

father's spinster sister, Aunt Betty (1698-1781). He also found time

to flirt with several of the young ladies of Buchan! With rest, he

recovered, but remained prone to arthritis if he overtaxed his

leg.

Pattie returned to the Greys in August 1763. He spent the next 5

years travelling around Britain with them from Kelso as far south as

Kent and East Sussex on garrison and policing duty (there was no

regular police force until the 19C.). In 1766, Pattie twice visited

France. On his first visit, he went to see the Jacobite Lord Ogilvy,

widower of his cousin Margaret Johnstone. On the second trip, he

intended to study at a French military academy in Angers, but was

sidetracked by the social life of Paris.

In 1768, Pattie bought a company in his cousin Lieut. Col.

Alexander Johnstone's regiment, 70th Foot. The commission was cheap,

since the regiment was sailing for the West Indies, for garrison duty

on islands ceded by the French in 1763. Pattie arrived in spring

1769. He combated scurvy among his troops by making them cultivate

their own fruit and vegetables. He also taught himself to play the

fiddle. Taking a lead from his cousin Colonel Johnstone, who had

purchased a plantation, Pattie bought a sugar estate for the family

at Castara on Tobago.

But by 1771 his health was suffering. Circumstancial evidence

suggests his arthritic leg was troubling him again. He returned to

Britain via either Boston or New York in 1772, before the rest of his

regiment took part in quelling the Carib Revolt. His younger brother

George sailed out to replace him as "laird" of Castara.

Pattie was living in London in 1773. In 1774, he took part in a

training camp for Light Infantry at Salisbury, organised by General

Sir William Howe, who had established permanent light companies in

the army in 1771. Pattie's interest in and aptitude for light

infantry work drew Howe's attention even at this early stage - and

Howe would remember him 2 years later. It was apparently after this,

c. 1775, that Pattie embarked upon designing the Ferguson Rifle, a

modification of Chaumette and Bidet's breechloading system for

military use.

At the turn of 1775-6, Pattie was back in Scotland. In April, he

went to London to try to interest Lord Townshend in his rifle design.

He eventually succeeded, and by May was at the Tower of London,

supervising the making of trial models and taking part in tests

before leading generals and dignitaries. The trial on 1 June received

full coverage in the Annual Register. On 4 July, while the Rebel

Continental Congress voted for independence and sent its declaration

for publication, Pattie was in Birmingham supervising the manufacture

of the first 100 Ferguson Rifles made for military service.

Pattie presented the King with sketches and a description of the

rifle. Via Major Cuyler, Howe's ADC, he received the General's

backing, and petitioned the King to command an experimental rifle

corps in the Colonies.

The rifle patent was approved on 2 December 1776, and he also

received private orders from individual officers and the East India

Company for rifles. These helped his finances: he had got into debt

through paying for the early models and trials from his own Captain's

pay, and had borrowed money from relatives to pay for the patent. He

was already working on a small field-gun.

In January 1777 he received permission from Townshend and General

Harvey to train 200 recruits at Chatham for his experimental corps.

However, with news of defeats at Trenton and Princeton, he was

ordered to make ready more quickly, with only 100 men. He officially

received his command on 6 March. His instructions were that at the

end of one campaign, he and his men were to be returned to their

original regiments, unless Howe specified otherwise.

In March 1777, Pattie and his corps sailed on the

Christopher to New York, where they arrived on 26 May. The

experimental field piece blew up in its first test, having been sent

out with the wrong size of ammunition. However, the corps - uniformed

in the green cloth which had been sent out with them - saw some

action in New Jersey. They took part in the expedition to the

Chesapeake, where Howe, a light infantry enthusiast, was impressed

with them. He assured Pattie that he intended to expand the rifle

corps. Unfortunately, events at Brandywine

on 11 September 1777 ended these prospects.

Ferguson's Corps performed well in the battle, fighting alongside

the Queen's Rangers, under James Wemyss. Pattie had the chance to

pick off a important-looking Rebel officer, but declined to do so for

reasons of honour. He was later told in hospital that the officer may

have been Washington, but this cannot be proven with certainty.

(Knowing the sense of humour some medics have, it may have been a

wind-up...) Pattie, at any rate, believed it was, and wrote, "I am

not Sorry that I did not know all the time who it was". There were

graver matters on his mind.

Moments after the alleged encounter with Washington, a musket

ball shattered Pattie's right elbow-joint. He spent the winter in

Philadelphia, under threat of amputation. He endured numerous

unanaesthetised operations to remove bone splinters which repeatedly

broke open his wounds. In November, he also received news of his

father's death in June. Yet in letters home, he bravely made jokes

about his operations.

But

he was never again able to wield his limbs as before. His right arm

was crippled, permanently bent at the elbow: he later received the

King's Bounty for its effective loss. He therefore learned to write,

fence and shoot left-handed. It was 13 May 1778 before he was fit to

return to duty - still wearing a sling. His rifle corps had been

disbanded This fact has given rise to a variety of dubious conspiracy

theories, especially in American secondary works: claims that the

corps was suspended because of Howe's 'jealousy', & c., but this

is dubious, to say the least. The rifle company had been set up as an

experiment, a field trial for one campaign only. As already noted,

Patrick's orders were that he was to return to his own regiment at

the end of that campaign, unless Howe "should have a further occasion

for his services". What further services could be expected from a

rifleman with a smashed arm, threatened with amputation? Under 18C

medical conditions, it was not unreasonable to assume he would never

again be fit for command. Besides, Howe, who had talent-spotted him

in 1774, and been supportive, was on the point of returning to

Britain just as Pattie returned to duty. Similarly, the oft-touted

(American) idea that the corps' disbandment turned the course of what

was now a world war does not bear scrutiny.

But

he was never again able to wield his limbs as before. His right arm

was crippled, permanently bent at the elbow: he later received the

King's Bounty for its effective loss. He therefore learned to write,

fence and shoot left-handed. It was 13 May 1778 before he was fit to

return to duty - still wearing a sling. His rifle corps had been

disbanded This fact has given rise to a variety of dubious conspiracy

theories, especially in American secondary works: claims that the

corps was suspended because of Howe's 'jealousy', & c., but this

is dubious, to say the least. The rifle company had been set up as an

experiment, a field trial for one campaign only. As already noted,

Patrick's orders were that he was to return to his own regiment at

the end of that campaign, unless Howe "should have a further occasion

for his services". What further services could be expected from a

rifleman with a smashed arm, threatened with amputation? Under 18C

medical conditions, it was not unreasonable to assume he would never

again be fit for command. Besides, Howe, who had talent-spotted him

in 1774, and been supportive, was on the point of returning to

Britain just as Pattie returned to duty. Similarly, the oft-touted

(American) idea that the corps' disbandment turned the course of what

was now a world war does not bear scrutiny.

Pattie accepted that he would have to wait until he returned to

Britain before he could devote more time to perfecting his rifle, and

does not seem to have lost much sleep over it. He was less obsessive

about that particular project than many later American writers on it

have been. He threw his energies into building a working relationship

with Howe's successor, Sir Henry Clinton. His first engagement since

he was disabled was the battle of Monmouth,

NJ (thanks again,

Glenn!), but his

rôle in it remains obscure. Back in New York, he impressed

Clinton with treatises on strategy and military ethics. He was given

command of a new unit of light troops, a mixed command of regulars

and Loyal Americans. Barely a year after he was disabled, he led them

on daring raids against Rebel salt works and privateer bases at

Chestnut Neck and Egg Harbor in New Jersey (15 October 1778). Heavy

casualties were inflicted on the enemy, but he tried to avoid harming

civilians.

That winter in New York, Pattie wrote satirical essays for

Rivington's Royal Gazette as

Egg-Shell (in riposte to Pulaski's self-justifying account of

Egg Harbor), John Bull and Memento Mori, published in

several issues through November and December. As it is the shortest

of the pieces, and one of the most deliciously sarcastic, here is

Egg-Shell:

The Royal Gazette, publ.

by James Rivington, New York, no. 220,

Saturday 7 November 1778, p. 3:

New-York, November 7.

Extract of a letter from General Count Polaski, to the

President of the Congress, dated October 16, 1778.

"SIR,

For fear that my first letter concerning my engagement should

miscarry or be delayed, and having other particulars to mention, I

thought proper to send you this letter.

"You must know that one Juliet an officer, lately deserted from

the enemy, went off to them two days ago, with three men whom he

debauched and two others whom they forced with them, the enemy

excited without doubt by this Juliet, attacked us the 15th instant,

at three o'clock in the morning, with 400 men. They seemed at first

to attack our pickets and infantry with fury, who lost a few men in

retreating; then the enemy advanced to our infantry. The Lieutenant

Colonel Baron de Bose, who headed his men and fought vigorously, was

killed with several bayonet wounds, as well as the Lieutenant de la

Borderie, and a small number of soldiers and others were wounded.

This slaughter would not have ceased so soon, if on the first alarm I

had not hastened with my cavalry to support the infantry, which then

kept a good countenance. The enemy soon fled in great disorder, and

left behind them a great quantity of arms, accoutrements, hats,

blades, &c.

"We took some prisoners and should have taken many had it not been

for a swamp through which our horses could scarce walk:

Notwithstanding this we still advanced in hopes to come up with them,

but they had taken up the planks of a bridge for fear of being

overtaken, which accordingly saved them; however, my light-infantry

and particularly the company of rifle-men, got over the remains of

the plank and fired some vollies on their rear. We had the advantage

and made them run again, although they were more in number.

"I would not permit my hunters to pursue any further, because I

could not assist them, and they returned again to our line, without

any loss at that time.

"Our loss is estimated, dead, wounded and absent, about 25 or 30

men, and some horses. That of the enemy appears to be much more

considerable. We had cut of the retreat of about 25 men, who retired

into the country and the woods, and we cannot find them; the general

opinion is, that they are concealed by the tories in the

neighbourhood of this encampment."

In Congress, 17th October, 1778.

Ordered to be published,

HENRY LAURENS, President.

To the PRESIDENT of the CONGRESS.

SIR,

AS you have thought proper to favour the public with a letter from

General Comte Polaski, in explanation of one previously wrote by that

gentleman, concerning what he is pleased to call his late engagement;

(altho' I have generally understood that term to imply a little

fighting) and as the second letter, which alone has been

produced, leaves the public almost as much at a loss as that which

remains buried in the dark and hollow bosom of the Congress; give me

leave to present you with a few remarks, until the Comte shall be

pleased to do it the justice he meant for the first, by sending an

interpretation of his own to attend upon it.

First then, sir, - Had not the Comte, by the bad choice of his

cantonments and neglect of measures necessary for their security,

invited an enemy to insult him with a certainty of impunity, persons

coming from him could scarce have prevailed upon a small detachment

of foot, without either artillery or support, to have committed

itself in a country so near the imperial seat of the mighty Congress,

among a body of foot, horse and field artillery, known to be many

times its number, exclusive of the militia of the province of Jersey,

which must have become pretty numerous after a ten days

invasion, unless indeed the Congress has entirely lost its credit

and authority, and the people have learnt to distinguish their

real enemies.

Secondly - Had the Comte ever been near to the detatchment that

attacked and took entire possession of the quarters of the three

companies that composed the infantry of his legion, he would have

discovered that it did not amount to two hundred men, exclusive of

fifty that remained a mile behind for the protection of the bridge,

which the Comte so obligingly lent to them for a spare hour;

or indeed had he or any of his surviving officers, amidst the variety

of fireings, pursuits and military evolutions, in which it seems they

were in a very secret manner employed that morning, approached within

view either of their enemy's or of the boats in which they

reimbarked, they would neither have deceived themselves nor their

august masters in this manner.

Thirdly, had the Comte joined his infantry in any reasonable time,

he must have added, that all their quarters were not only forced, but

every officer and man in them cut off, except a few who escaped

unarmed to conceal themselves in the neighbouring brakes, and some

prisoners who, after the success of the attack was certain, were

saved from the bayonnets of the soldiers.

The Comte pays no great compliments to his corps, when he says,

that only two officers (out of nine that were with his infantry)

stood to hazard their lives in trying to rally their men. In his next

letter of amendments he ought in justice to inform you, that seven

lost their lives on that occasion.

To save him the trouble of recollection the following are the

names of five of them:

Lieutenant Colonel Bose,

commanding the infantry.

Captain Fray, of the first company.

Captain Zecont of the second company.

Lieutenant Broderie, and

Lieutenant Stegs of the light-horse.

There were two other Lieutenants left for dead in their quarters,

but the prisoners, altho' they knew the faces, did not recollect the

names which were foreign.

And with regard to his loss in men, which it is humbly presumed

amounts to two thirds of his infantry, you will be enabled to form a

better idea of it, if you can prevail upon him to give in a return of

the number of infantry now really existing in his corps. - Had

the detachment been able to arrive at three o'clock, as the

Comte supposes, it would possibly have found time to visit the

stables, and to silence the fieldpiece with which he was amusing

himself in firing alarm guns from time to time to solicit his

neighbour Col. Proctor to his assistance. But the attack was not made

till near five, and day opened whilst the British soldiers having no

enemy before them, were ransacking the quarters of his late infantry.

There is always on such occasions a moment before the officers can

re-assemble their men, when a ready and enterprizing enemy may try

what stuff their assailants are made of: But for such a purpose,

there must be an officer capable of forming his plan instantly and

executing it resolutely, followed by men fit for a close jostle in

the dark. - Had the Comte and his horse been equal to such a task,

his enemies would at least have had occasion to discharge their

pieces, and would probably have had some men wounded, and possibly

some killed before he was repulsed. As it was, the Comte will be

pleased to allow that he had no occasion to hurt the wind of his

horses in the pursuit, and that his enemies moved off with a gravity

and leisure which could only be equalled by the modesty and respect

with which they were followed. He will also allow that the rear

guard, further to prevent unnecessary hurry and fatigue to his

horses, halted repeatedly in a very open and sound ground, even

before they reached the swamp and bridge which he with so much reason

complains of; and he will further allow that they spent a full hour

and a half in a retreat not exceeding two miles, so as to afford an

opportunity for his cavalry of coming within random shot at least,

without putting their horses to a trot, had they been so

inclined.

In one respect however, to be candid, the Comte is right, his

enemies did withdraw from him; yet whatever opinion he may have

formed they certainly never meant to pass the season there, but only

to pay him a civil visit, and take their leave before they were

introduced to too many of his neighbours; not that they had any

objection to be accompanied a part of the way, in the very polite and

respectful manner in which he knows so well to behave to - his

friends.

As I wish not entirely to engross a subject which may be so much

better adorned by Comte Polaski's own illustrations, I shall leave

for him the following queries.

At what pace did his horse pursue? did they ever approach near

enough to exchange a shot?

What number did he kill? what number did he take, and how many

wounded were left behind in the flight?

Whether the wicked tories (who must be bewitched, not to reclaim

under so mild and free a government) have yet given up the five and

twenty men whose retreat he cut off? for we are made to believe that

there were only three men of the British detachment missing that

night, one of whom, a deserter, has enlisted in the Continentals,

another who it is presumed would rather smell strong if kept prisoner

above ground, and a third, who possibly in the confusion of a night

scramble may have lost himself, and remain the Compte's prisoner.

I have only to add that I am happy in affording Comte Polaski an

opportunity of so easily refuting the assertions above mentioned, by

producing the afore named officers of his legion said to be killed,

and the wounded men and other made prisoners by him in the various

actions he describes of that morning,

An officer who, in an unlucky or unguarded moment, should meet

with a misfortune to affect his military character, although even

exerting himself in a bad cause, will command the forbearance, if not

the sympathy, of his adversaries, providing he apologizes for his

conduct with modesty and candor; but if he should so far forget his

situation as to assume a merit, and make a triumphant recital,

founded on the grossest misrepresentation, concerning what a man of

reflection and feeling would naturally wish to have forgot, he has no

farther claim to commiseration.

EGG-SHELL.

Pattie associated with the Peace Commissioners, including his

cousin Commodore George Johnstone, and their Secretary Professor Adam

Ferguson of Edinburgh University, a family friend (no relation),

later his first biographer.

Early in 1779, Pattie led reconnaissance and mapping missions in

New York and New Jersey. His warnings to Clinton about the weak

fortifications on the Hudson were confirmed when Stony

Point fell to the Rebels on 16 July. On its return to British

hands 2 days later, he was given the task of refortifying it. Clinton

appointed him Governor and Commandant of Stony Point and of

Verplanck's Point on the opposite bank. Pattie expended much time and

effort on this post, only to be ordered to dismantle the works and

withdraw in autumn.

In December he was given command of the American Volunteers, made

up of New York and New Jersey Loyalists. They set sail on 26 December

1779, landing at Tybee a month later. On 7 February 1780 at Savannah,

Clinton formalised Pattie's provincial brevet as Lieutenant Colonel

of the American Volunteers, backdated to the beginning of December.

While in Savannah, Pattie drew up designs for refortifying the

city.

On 14 March, Pattie was bayoneted through the left arm in a

'friendly fire' incident at MacPherson's Plantation, SC, when Major

Charles Cochrane and the British Legion infantry mistook his

encampment for that of the enemy. For 3 weeks, he had limited use of

his one good arm, but chivalrously forgave Cochrane.

During the siege of Charleston, Pattie worked closely with

Banastre Tarleton (1754-1833)

and the Legion horse, under Lieut.

Col. James Webster (1740-81), 33rd Foot, to cut off Rebel supply

routes. Pattie and 'Ban' worked well together, and, contrary to myth,

respected each other. Pattie regarded Tarleton, a Liverpool

merchant-shipping magnate's son, as "a very active gallant young

man", and the latter wrote well of him in his Campaigns. They

defeated Huger at Monck's Corner on 14 April. But that night a couple

of drunken Legion troopers, celebrating the victory, broke into Fair

Lawn Plantation and terrorised Jane Giles - a young Englishwoman

whose first husband had been Sir John Colleton, Bt. - and her 3

companions, of of whom, Anna Fayssoux, the wife of a Rebel army

surgeon, was sexually assaulted. Pattie sent men to arrest the

culprits, intending to execute them. Webster commuted the sentence to

flogging - if 'commuted' is the phrase for a punishment which could

kill more slowly. Ban supported the punishment of the offender. Mrs.

Giles (still often called "Lady Colleton") was a Loyalist.

Politically, it would have been damaging to let the incident go

unpunished. But from this incident, which actually preceded Pattie's

generous description of Ban, 19C American writers such as Washington

Irving and Lyman C. Draper derived the myth of enmity between the two

officers. This has been perpetuated by later writers.

On 18 April, Clinton confirmed Pattie in a permanent promotion, a

Majority in the 71st Foot (Fraser's Highlanders), back-dated to the

previous October. Pattie therefore gave up his brevet Lieutenant

Colonelcy, although he never served with the 71st Foot as a

regimental officer.He and his American Volunteers took part in the

capture of Fort Moultrie, of which they took command on 16 May, 4

days after the surrender of Charleston. He began to devise plans for

erecting fortifications to defend all the principal roads and

communications by land and sea in the province.

On 22 May, Pattie was appointed Inspector of Militia by Clinton,

to recruit and train local Loyalists, a post for which he refused to

accept any additional pay. He left Charleston on 26 May to march up

country. In June, he raised a regiment of 240 men at Orangeburg, but

his base for most of that summer was around Fort Ninety-Six. The

militia flocked to him, and he began training them to respond to

signals from his light infantry silver SILVER

WHISTLE...

Clinton had by now been succeeded by Charles, Lord Cornwallis, as

commander in the South. Cornwallis was less enthusiastic about using

militia, and also generally favoured his own appointees. This caused

problems for Pattie, since one of them, Lieut. Col. Nisbet Balfour

(1744-1823), was Commandant at Ninety-Six. Pattie had begun designing

fortifications for Ninety-Six, which he had forwarded directly to

Cornwallis and Clinton, not via Balfour, who often complained about

him in his letters to Cornwallis. But by August, rivalries at

Ninety-Six had eased. Balfour was posted to Charleston and replaced

by Col. John H. Cruger, a New Yorker. Work on Ninety-Six's defences

was under way by early September.

Pattie's men had been pursuing Clarke, who defeated Loyal militia

at Musgrove's Mill on 18 August. At Winn's Plantation the next day,

Pattie learned of the victory at Camden. He then set out to pursue

Sumter, but on 21 August learned that Tarleton had surprised and

defeated the 'Gamecock' at Fishing Creek. On 23 August, Pattie rode

to Camden to get new instructions from Cornwallis. He was to operate

on the left flank, detached from the main body of the army: to aid

the Loyalists, and forage from and punish the Rebels. Cornwallis had

misgivings about his chances, yet nevertheless authorised him to do

this - a decision he would regret, and for which Sir Henry Clinton

later castigated him.

Pattie marched his men up into North Carolina on 7 September.

Leaving most encamped, he took 50 American Volunteers and 300 militia

towards Gilbert Town and Cane Creek, to surprise McDowell. But

McDowell, like Clarke, Shelby and Williams, had withdrawn into the

Back Country. Pattie paroled a prisoner to warn these Rebels "that if

they did not desist from opposition... he would march his army over

the mountains, hang their leaders, and lay their country waste with

fire and sword". Shelby passed on the message to Sevier, of the

Washington County Militia. They mobilised the other militias along

the Watauga. At Sycamore Shoals on 25 September, they were joined by

forces from Georgia, Virginia and the Carolinas. Incited by the

fanatical Rev. Samuel Doak's sermons to wield "the Sword of the Lord

and of Gideon" in a holy war, they intended to destroy Patrick

Ferguson and his army. The son of Enlightenment Edinburgh was to face

a force motivated by the 17C militant bigotry own country had

outgrown.

Meanwhile, Pattie won numerous people over to the Loyal cause. On

24 September, 500 men came in. He and his troops left Gilbert Town on

27 September. He learned of the large Rebel advance from deserters

from Sevier. Pattie wrote to Cornwallis, then in Charlotte, and to

Cruger at Ninety-Six for support. Cruger could spare none, and

advised retreat. On 1 October, at Denard's Ford, Pattie wrote to

Cornwallis that more Rebels were mustering. He reported that two old

men - survivors of a party of 4 - had just been brought into camp

"most barbarously maimd by a Party of Clevelands Men". The incident

angered him: he used it in an impassioned proclamation that day to

rally the Loyalists:

- Gentlemen: Unless you wish to be eat up by an inundation of

barbarians, who have begun by murdering an unarmed son before the

aged father, and afterwards lopped off his arms, and who by their

shocking cruelties and irregularities, give the best proof of

their cowardice and want of discipline; I say, if you wish to be

pinioned, robbed, and murdered, and see your wives and daughters,

in four days, abused by the dregs of mankind - in short, if you

wish or deserve to live, and bear the name of men, grasp your arms

in a moment and run to camp.

- The Back Water men have crossed the mountains; McDowell,

Hampton, Shelby and Cleveland are at their head, so that you know

what you have to depend upon. If you choose to be pissed upon

forever and ever by a set of mongrels, say so at once and let your

women turn their backs upon you, and look out for real men to

protect them.

He began to withdraw towards Charlotte, and wrote to Cornwallis

requesting support. The Legion could not be sent out immediately,

because Tarleton had been seriously ill with yellow fever or malaria,

and was still weak. Instead, Cornwallis ordered Pattie to rendezvous

with Major Archibald McArthur and the 71st at Arness Ford.

On 6 October, Pattie and his troops set off towards Charlotte,

but encamped at King's Mountain (now a National

Park), to wait for McArthur's approach. An anecdote collected by

Draper in 1874 suggests Pattie spent his last evening with his 2

doxies, Virginia Sal - a buxom young redhead - and Virginia Poll or

Paul(ina). Another of Draper's correspondents, Wallace Moore

Reinhardt, suggested one may have been a Miss Featherstone, and their

shared epithet suggests they may have been Loyal refugees from

Virginia.

The following afternoon, the Rebel forces surrounded King's

Mountain and launched a surprise assault. Incited by Doak's sermon,

and by exaggerated reports that Tarleton had 'massacred' Buford's

command at Waxhaws in May, their countersign was "Buford". The

implication was "No quarter" for Ferguson and his men - or his women.

Sal's bright red hair made her an easy target: among the first

casualties, she was shot as she helped one of the wounded to the

tents.

The Loyalist militia, running low on ammunition, began to fall

back. Some seventy uniformed American Volunteers bore the brunt of

the fighting. They raced from one side of the mountain to the other,

making bayonet charges that thrice succeeded in driving back the

Rebels - but only briefly. Pattie was in the thick of the action,

sword in hand, riding to the weakest points of the line to rally his

men, signalling with his famous whistle. Two horses were shot from

under him. He took a third. It was a grey: his career had come full

circle.

Knowing that there was scant hope of quarter, he swore he "never

would yield to such a damn'd banditti". With two other mounted

militia officers, Colonel Vezey Husbands and Major Daniel Plummer, he

led a last, desperate attempt to break the enemy line, and, sword

drawn, spurred his horse forward - into a blaze of rifle-fire.

Husbands was killed outright, Plummer badly wounded. Pattie

himself was a conspicuous target, with his sword in his left hand,

his bent-up right arm, and a checked duster-shirt protecting his

uniform. A massive volley blasted him from the saddle. About a dozen

balls shattered his body. His foot caught in the stirrup of his horse

as he fell, and he was dragged along the ground. He died within

minutes, in the arms of his friends. Jubilant Rebels stripped and

urinated on his corpse, before his orderly Elias Powell and other

companions were allowed to bathe and shroud him in a raw

beef-hide.(¡Grande hazanas - Con muertos! to quote

Goya in a later war...) He was buried in a shallow grave, beside

poor Sal, from whose corpse a Rebel took a necklace of glass beads.

Poll was taken prisoner, but released at Moravian Towns and returned

to the army in Charlotte, where she apparently found a new

protector.

"Don't kill any more! It's murder!" the Rebels' nominal

commander, William Campbell protested as, with cries of "Give them

Buford's play!" and "Tarleton's Quarter!", they ignored the

Loyalists' white flags. Only with great difficulty did he prevent a

wholesale massacre. Rebel casualties were 28 dead and 64 wounded, but

157 Loyalists were killed, and 163 so seriously hurt that they were

abandoned on the mountain. Some were rescued by local Loyalists, and

nursed back to health. Others were less fortunate: for weeks

afterwards, turkey-buzzards, wolves and hogs fattened themselves on

human carrion.

The rest - nearly 700 men, including walking wounded - were

marched off as prisoners. Along the way, they were ill-used, even

hacked with swords. Campbell had to order his officers to "restrain

the disorderly manner of slaughtering and disturbing the prisoners".

At Red Chimneys - plantation of Aaron Bickerstaff, a Loyalist Captain

mortally wounded in the battle - nine militia officers were hanged

from a tree after 'trial'. Another man was hanged for trying to

escape. Cleveland beat up Uzal Johnson, the young New Jersey doctor,

"for attempting to dress a man whom they had cut on the march", his

friend Lieutenant Anthony Allaire (American Volunteers), wrote.

Tarleton and the Legion arrived 3 days too late, and learned the

worst. Ban later wrote in his Campaigns: "the death of the gallant

Ferguson threw his whole corps into total confusion... The

mountaineers, it is reported, used every insult and indignity, after

the action, towards the dead body of Major Ferguson, and exercised

horrid cruelties on the prisoners that fell into their

possession."

News of Pattie's death reached his family about 10 days before

Christmas. His family was "disconsolable" at his loss - as are most

people who come to know him through his charming letters.

While his family lies in a mausoleum

in Edinburgh, the "King of the Mountain" is still on King's Mountain.

Now, even the former enemy acknowledge his heroism.

Pattie was the only British serviceman in the battle: all the

others were Loyal Americans. Not all was lost, nor was the sacrifice

in vain. Some of them - including de Peyster and Allaire - later

settled in Canada - a country which still honours the contribution to

its development made by the refugees from the other Colonies, as you

will see if you check out the United

Empire Loyalists' Association website!

John Robertson has given us a

neuk on his site, where you can see other Pattie-related items,

here ! (Careful, though: this site is not altogether

lobster-friendly...)

Gravesite, King's Mountain, South

Carolina

- A high, grey cairn.What more

is to be said?

- Eagles have gone into their cloudy bed.

W. B. Yeats, Deirdre

The cairn on Pattie's grave post-dates the 1880 centenary. He

has a fine headstone, erected in 1930. The inscription is touching

and generous, even if it does get his rank and regiment wrong (the

modern HLI is not the same 71st as Fraser's Highlanders!), and

probably also his birthplace. (There were no Pitfour Fergusons of his

generation baptised at Old Deer in Aberdeenshire - he was probably

born in Edinburgh!) Sadly, 'Virginia Sal', the buxom young

redhead who lies with him, is not named on the monument. She was shot

while tending the wounded early in the battle. Her surname may have

been Featherstone.

TO THE MEMORY OF

COL. PATRICK FERGUSON

SEVENTY-FIRST REGIMENT,

HIGHLAND LIGHT INFANTRY.

---

BORN IN ABERDEENSHIRE,

SCOTLAND IN 1744,

KILLED OCTOBER 7, 1780

IN ACTION AT

KING'S MOUNTAIN

WHILE IN COMMAND OF

THE BRITISH TROOPS.

---

A SOLDIER OF MILITARY

DISTINCTION AND OF HONOR.

---

THIS MEMORIAL

IS FROM THE CITIZENS OF

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

IN TOKEN OF THEIR APPRECIATION

OF THE BONDS OF FRIENDSHIP AND

PEACE BETWEEN THEM AND THE

CITIZENS OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE.

---

ERECTED OCTOBER 7, 1930.

|

Photo: Holley Calmes.

Flag & flowers: Doc

|

Return to Top

Biography

Biography