Major

JOHN PITCAIRN,

Marines

1722/3-75

John (left) and Francis Smith

supervise the destruction of Rebel arms at Concord

Engr. by Amos Doolittle after Ralph Earl

John Pitcairn was baptised at St. Serf's, Dysart,

on 28 December, 1722 (Old Calendar - 1723, New Calendar): his date of

birth is not recorded separately, so it may have been the same day.

He was the youngest surviving child of the Rev. David Pitcairn, M. A.

(St. Andrews), former regimental chaplain to the Cameronians and

veteran of Blenheim, who served as minister of Dysart for 49 years,

and his wife Katharine Hamilton of Wishaw.

In his early 20s, John married Elizabeth Dalrymple (1724-1809).

Their first child, Annie, was born in Edinburgh in 1746, in which

year John was commissioned Lieutenant in Cornwall's 7th (Marines)

Regiment.

Soon after that, however, the Marines were disbanded. When they

were established permanently in 1755, John's Lieutenancy was

reconfirmed. The following year, he was promoted Captain. He served

during the Seven Years' War, and in 1757 (when his father died, and

his daughter Johanna was born in Dysart) was aboard the warship

H.M.S. Lancaster - presumably en route to Canada, where the

Lancaster was involved in the taking of Louisbourg. The Pitcairns

moved down from Edinburgh to Kent in the early 1760s, when John

became permanently attached to the Chatham division of Marines.

John

and Betty had six sons (one of whom, Clerke, died young) and four

daughters. Their Dysart-born eldest son, David, followed his uncle

Dr. William Pitcairn to become an eminent physician at Bart's, and,

eventually, physician to the Prince Regent. Physically, it was he who

most closely resembled his father. In 1786, when the American artist

John Trumbull came to London to make sketches for his painting

The Death of General Joseph Warren at Bunker

Hill, he based his likeness of John upon Dr. David. (The

detail shown here links to Ed the

Saint's site) Robert, born in Burntisland, became a

midshipman. In 1767 he sighted the Pacific island named in his

honour, but was lost at sea in 1770, aged only 17. William, born in

Carnbee, followed his father into the Marines, while Thomas joined

the army. The girls - Annie, Katharine, Johanna and Janet - all

married army or naval officers of good family. The youngest child,

Alexander, born in Kent in 1768, eventually became a barrister in

London.

John

and Betty had six sons (one of whom, Clerke, died young) and four

daughters. Their Dysart-born eldest son, David, followed his uncle

Dr. William Pitcairn to become an eminent physician at Bart's, and,

eventually, physician to the Prince Regent. Physically, it was he who

most closely resembled his father. In 1786, when the American artist

John Trumbull came to London to make sketches for his painting

The Death of General Joseph Warren at Bunker

Hill, he based his likeness of John upon Dr. David. (The

detail shown here links to Ed the

Saint's site) Robert, born in Burntisland, became a

midshipman. In 1767 he sighted the Pacific island named in his

honour, but was lost at sea in 1770, aged only 17. William, born in

Carnbee, followed his father into the Marines, while Thomas joined

the army. The girls - Annie, Katharine, Johanna and Janet - all

married army or naval officers of good family. The youngest child,

Alexander, born in Kent in 1768, eventually became a barrister in

London.

In the Marines, unlike the army, commissions were not purchased,

and so it was only in 1771, aged 48, that John reached the rank of

Major. In early December 1774, as unrest spread in the Colony of

Massachusetts, he arrived in Boston with some 600 Marines drawn from

all three divisions: Chatham, Portsmouth and Plymouth. He had to

contend with a dispute between Admiral Graves and General Gage over

landing them, and the fact that they had no proper winter clothing

and equipment.

The Plymouth Marines had been sent out with inadequate officers,

who could not keep order. As a result, they proved an ill-disciplined

trial. Indeed, when John got them ashore, he was astonished by the

Marines' poor appearance in comparison with the army. He wrote to the

Admiralty, suggesting an end to the recruitment of men under 5' 6".

He also observed that issuing uniforms with white facings were not a

good idea, given the men's difficulty in keeping themselves

clean.Some Marines were selling their kit to buy the lethal local

rum, which killed a number of them. John spent several weeks living

in barracks with them to keep them sober. He was a humane man, to

whom harsh punishments went against the grain. The fact that he had

to have some of the Plymouth "animals" (his word!) flogged distressed

him. Respected and popular, he eventually succeeded in drilling them

into an effective force.

John was billeted on Francis Shaw, a fiercely anti-British

tailor, neighbour to Paul Revere on North Square, and ancestor of the

Civil War hero Robert

Gould Shaw. Remarkably, despite their political differences, he

won over his reluctant host on a personal level. According to Shaw

family tradition, John prevented a duel between young Lieutenant

Wragg, also billeted on the household, and Sam, Shaw's equally

hot-tempered teenaged son. The Lieutenant had made some anti-Rebel

remarks, and Sam had responded by throwing wine on him. Fortunately,

John was able to defuse the situation with his characteristic warmth

and good humour. Sam must have learned his lesson, since he later

became a diplomat!

Other Boston radicals also came to respect John's integrity,

honesty, and sense of honour, and trusted him to deal justly in

disputes between the locals and the military. His genial charm gained

their affection: even the Rebel preacher and propagandist Ezra Stiles

describing him as "a good man in a bad cause". Every Sabbath he

attended Christ Church, but during the rest of the week he was noted

for his profane language. He held salon at Shaw's house, where

British officers and locals, including Revere, could meet, socialise,

and exchange views in a civilised manner. He also had family company:

his sons William and Thomas - the former a Lieutenant in the Marines,

the latter in the Royal Artillery - and his daughter Katharine's

husband, Captain Charles

Cochrane, a younger son of Lord Dundonald.

On 19 April 1775, John Pitcairn was second-in-command of the

troops sent to destroy Rebel stores in Concord. At Lexington Green,

they came face-to-face with a body of armed American militia. John

ordered his men NOT to fire, and commanded the militiamen to

lay down their arms and disperse. They began to do so, but, as John

wrote in his report to Gen. Gage:

- ...some of the Rebels who had jumped over the Wall, Fired Four

or Five Shott at the Soldiers, which wounded a man of the Tenth,

and my Horse was Wounded in two places, from some quarter or

other, and at the same time several Shott were fired from a

Meeting House on our Left - upon this, without any order or

regularity, the light Infantry began a scattered Fire, and

Continued... contrary to the repeated orders both of me and the

officers that were present...

There is still controversy over the source of the first shot;

possibly provocateurs from extremist circles in Boston were involved.

Despite John's efforts to restore order, eight 'Minute Men' were

killed. The American War of Independence began as news of the

shootings spread to the neighbouring villages. After continuing and

fulfilling their mission to destroy the arms stores in Concord, the

British came under heavy fire on the road back to Boston. They

suffered severe casualties. At Fiske's Hill John's horse was again

grazed by bullets, and threw him. He was forced to march the rest of

the way, as the wounded animal had bolted into the American

lines.

It is alleged that the horse took with it his brace of richly

decorated metal scroll-butt pistols, made by John Murdoch of Doune.

The pistols were presented as a trophy to the Rebel officer Israel

Putnam. They are displayed in the Hancock-Clarke Museum in

Lexington during the tourist season, and off-season in The Museum

of Our National Heritage, also in Lexington. However, there is a

question-mark over their provenance: the heraldic crest engraved on

the escutcheon plates depicts three swords, with a snake twined

around the middle one. This does not resemble the known crest

of the Pitcairns of Forthar, a moon rising from a cloud. So whose the

pistols really were is uncertain.

On 17 June, the British launched 3 assaults on the American

position at Bunker Hill (actually on Breed's Hill) at Charlestown,

near Boston, and won the day - but at horrific cost: 50% killed and

wounded. Even the surgeons were horrified at the number of double

leg-amputations needed because the Rebels, low on bullets, had

stuffed their guns with broken glass, nails, and scrap metal.

Among the casualties was John Pitcairn. In the summer heat he led

his Marines - including his own sons - on foot up the hill, to take

part in the third attack. While advancing, they crossed another line

of infantry, who were being pushed back by heavy Rebel fire. John

told them to "Break, and let the Marines through!", and, more

colloquially, is said to have threatened to "bayonet the buggers" if

they would not! Waving his sword, he urged his men on: "Now, for the

glory of the Marines!" - Then a musket-ball smashed into his breast,

and he collapsed into William's arms. While the Marines charged

forward in the final assault, the young Lieutenant carried his

wounded father out of the line of fire, before returning to the

battle. The boy was so bloodied that some witnesses thought that he

himself was hurt.

John was taken by boat back to Boston, and put to bed in a house

on Prince Street. He was conscious, but, experienced veteran that he

was, he knew his chances were poor. The army surgeons were overworked

because of the heavy casualties, so General Gage, anxious to save a

valued officer, sent a Loyalist town physician, Thomas Kast, to tend

him. John told Dr. Kast - at 25, of an age with his own doctor son -

that he was bleeding internally and would die soon. Kast asked him

where he was hurt. He placed his hand upon his chest: "Here". The

young doctor suggested that it might not be fatal, and made to turn

down the sheet, but John refused to move his hand. Kast tried again;

still the Major kept his hand pressed over the sheet across his

wound. Firmly but courteously, he asked him not to touch him until he

had set his affairs in order. Only then did he submit to an

examination. But when Kast pulled John's waistcoat away from his

breast, the blood gushed out, staining the floor. The wound was

dressed, but within a couple of hours, while Kast reported back to

the General, John died from the effects of the hæmorrhage. He

was 52.

When William told the Marines: "I have lost my father!", some of

them responded: "We have all lost a father!" Mourned by friend and

foe alike, Major John Pitcairn was buried in the crypt of Christ

Church, 'the Old North Church', in Boston. The fatal bullet and his

uniform buttons were returned to Betty and the children - the

youngest of whom, Janet and Alexander, were aged only 14 and 7

respectively.

There is no authentic portrait of John Pitcairn, other than a

cartoonish image by Earl and Doolittle. The frequently reproduced

miniature, charming though it is, is too late, judging by the style

of the uniform. It may represent his son Thomas; or else be derived

from the 1786 Trumbull painting, for which Dr. David posed.

Old North Church, Boston, Mass.

It has been alleged that in 1791 the family sent for John's body

to be reinterred in his brother Dr. William Pitcairn's vault at St.

Bartholomew the Less in London. The story goes that a Boston doctor,

Amos Windship, a notorious conman and crook, exploited the Pitcairns

for personal gain, and sent them another body instead. However, the

Old North Church in Boston is sure it has got the real John

Pitcairn, and there is no entry in the burial register at

Bart's about the alleged re-interment. The only Pitcairns buried

there are John's brother Dr. William (d. 1791), son Dr. David

(1749-1809), Betty Dalrymple, John's widow, who outlived her son by

only a month (1724-1809), and David's widow, Elizabeth Almack

(1759-1844). So this looks very much like an old wives' tale.

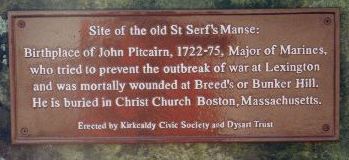

There is a modern-looking plaque in Old North Church, Boston. It

mistakenly refers to his corps as 'Royal Marines' - the 'Royal'

designation was granted in the early 19C:

Major John Pitcairn

Fatally wounded

while rallying the Royal Marines

at the Battle of Bunker Hill

was carried from the field to the boats

on the back of his son

who kissed him and returned to duty

He died June 17, 1775 and his body

was interred beneath this church

Photo: Frank

Collins

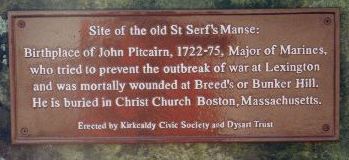

Dysart, Fife.

John's birthplace, the old manse of Dysart, was demolished over a

century ago. The marble plaque John erected to his parents' memory in

1757-8 in St. Serf's was destroyed by vandals in the early nineteenth

century, after the kirk fell into ruin. As a result, until recently

there was nothing to commemorate John in his hometown.

Photo: M M

Gilchrist

For the past couple of years I have been working with the

Kirkcaldy Civic Society and the Dysart Trust to get a plaque

installed in John's memory near the site of the old manse. On

Saturday 13 April 2002, it was unveiled in a small ceremony involving

Ann Watters and Jim Swan of the KCS and Dysart Trust respectively,

genealogist Mrs. Sheila Pitcairn, and yours truly. John is now the

first of 'our boys' to get a memorial plaque here in Scotland!

Anne Watters, Kirkcaldy Civic Society,

speaks.

Yours truly.

Sheila Pitcairn performs the unveiling

honours.

Return to Top