Michael von Elphberg: An Appreciation

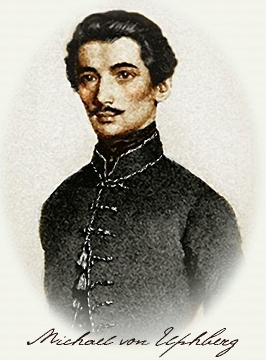

Friedrich (Fritz) von Tarlenheim, c. 1876

So - was Michael von Elphberg, Duke and Governor of Strelsau, as

'Black' as painted?

So - was Michael von Elphberg, Duke and Governor of Strelsau, as

'Black' as painted?

George Featherly (friend of Hon. Rudolf Rassendyll, on staff of British Embassy in Paris) described Michael - who, it must be recalled, was still extremely young (under 27) at the time of his tragic death:

"a great man"; "An extremely accomplished man, I thought him."

Frau ____ (innkeeper at Zenda, widow, mother-of-two):

The old lady, indeed, did not hesitate to express regret that the duke was not on the throne, instead of his brother.

"We know Duke Michael," said she. "He has always lived among us; every Ruritanian knows Duke Michael. But the King is almost a stranger; he has been so much abroad, not one in ten knows him even by sight."

Hon. Rudolf Rassendyll (quoting Oberst Sapt's snobbish establishment view of Strelsau's socio-economic and political divisions):

The city of Strelsau is partly old and partly new. Spacious modern boulevards and residential quarters surround and embrace the narrow, tortuous, and picturesque streets of the original town. In the outer circles the upper classes live; in the inner the shops are situated; and, behind their prosperous fronts, lie hidden populous but wretched lanes and alleys, filled with a poverty-stricken, turbulent, and (in large measure) criminal class.

These social and local divisions corresponded, as I knew from Sapt's information, to another division more important to me. The New Town was for the King; but to the Old Town Michael of Strelsau was a hope, a hero, and a darling.

As Rassendyll observed the protests at 'Rudolf V''s coronation in the Altstadt:

...the mass of the people received me in silence and with sullen looks, and my dear brother's portrait ornamented most of the windows - which was an ironical sort of greeting to the King. I was quite glad that he had been spared the unpleasant sight. He was a man of quick temper, and perhaps he would not have taken it so placidly as I did.

One is left with the lingering suspicion that Rassendyll was hijacked by the 'wrong' side. Who were Michael's enemies, when all's said and done?

- The Court clique around the dissolute Rudolf

- The Cardinal-Archbishop of Strelsau, representing the Church (in the era of Pius IX's notorious Syllabus of Errors, no. 80 of which rejected any notion of the Papacy coming to terms with "progress, liberalism, and modern civilisation")

- The military

- The wealthy privileged classes of the Neustadt

...which suggests he was doing something right (or rather, Left)!

What seems to be implicit, then, is a conflict between reform and absolutism in the years following the First International, the foundation of the German Social Democratic Party, and the defeat of the Paris Commune. We know from The Heart of Princess Osra that there was significant political unrest in Ruritania around the time of Rudolf V's infancy: the White Palace was destroyed in the 1848 Revolution, and Strelsau Public Gardens were laid out on its site. We also know that the preferred replacement for Michael as Governor of Strelsau was old Marshal von Strakencz. Yes: military rule for a city in which the working-classes were already "turbulent"... (And when and where, one wonders, did von Strakencz and Sapt win their medals? - Fighting against their own people in '48?) In short, the Duke's plan to depose Rudolf V in a fairly bloodless palace coup may well have been intended to forestall a potentially more desperate and violent turn of events. Had he led a popular uprising, the army would probably have turned the Strelsauer Altstadt into a slaughterhouse, like Paris.

Information on the Elphberg dynasty in The Heart of Princess Osra raises the possibility that Sapt (either from ignorance or by intent) may have misled Rassendyll as to the nature of Michael's ambitions. The Counts von Lauengram, as descendants of Rudolf III's younger brother Heinrich, would have had a claim to the throne superior to that of a merely morganatic line. Albert von Lauengram, last direct male heir of this junior line of the Elphbergs, was one of the Six, and was killed by Sapt's men at Zenda. It is surely possible that the initial plan was to install Albert as King in place of Rudolf, and for Michael to take over the Chancellorship (the post for which one suspects his father had been grooming him), which would have given him more political scope than merely being a King Consort to Flavia.

The 2 Cities of Strelsau

There are disturbing undercurrents in the personal hostility Rudolf's faction expressed towards the Duke. Michael - black-haired, brown-eyed, dark enough to have gained the epithet 'Black' - did not look like a 'proper' red-haired, blue-eyed, pale-skinned Elphberg. His mother was of "good" family, but not sufficiently "exalted" to be Queen, and there are hints that his parents' marriage was considered a mésalliance in other than class terms: Rassendyll, while in character as Rudolf, likened him (to his face!) to a "mongrel dog" (mischling in German - a word with an ominous future). Moreover, historically, the Elphberg dynasty tended towards unambiguously Teutonic masculine names: Rudolf, Heinrich, Albert. Michael's name, although popular among Catholics as that of the Warrior Archangel, is Hebrew. Viewed in the social and cultural context of late 19C Central Europe, cumulatively these suggestions imply that Michael's mother was of a high-ranking, converted Jewish family, and that the Ruritanian Establishment's hostility towards the boy was partly driven by anti-Semitism. This may have been a factor in his long-running dispute over precedence with the Cardinal-Archbishop of Strelsau.

Hope ultimately jolts reader-preconceptions in giving Michael a chivalrous, genuinely heroic death. Despite hints of failing health,* he was fatally wounded fighting to save a courtesan he did not really love from being raped by a treacherous ally. This overturns readers' assumptions that the Duke's non-participation in previous fighting was due to cowardice: in this crisis, he is shown to have been physically courageous to the point of recklessness. Despite the tremendous dramatic potential of a sword duel in a darkened room, his last scene has never been depicted properly on film - presumably because it would complicate viewer-loyalties.

*The fluctuating high colour in the cheeks, the burning brilliance of his eyes, and air of intensity are ominous signs to any reader of 19C fiction. Rassendyll did not spend enough time with him to mention a cough, but a 19C reader would perhaps pick up the hints that the champion of the Altstadt had contracted the most common disease of the urban poor: pulmonary tuberculosis. This would explain why he was in such a hurry politically (after all, he could have gone abroad for a couple of years, let Rudolf make himself unpopular enough to be deposed, and then returned triumphant at the people's bidding), and why he did little fighting in person.

Back to

TOP

The first cut won't hurt at all,

The second only makes you wonder...

- Propaganda, Duel