Victor Hugo, Notre Dame de Paris

…Here, breaking into sobs, and raising her eyes to the priest: "Oh! wretch, who are you? What have I done to you? Do you, then, hate me so? Alas! what have you against me?"

– "I love you!" cried the priest.

Her tears suddenly stopped, she gazed at him with the look of an idiot. He had fallen to his knees and was devouring her with an eye of flame.

"You understand? I love you!" he cried again.

"What love!" said the unhappy girl, shivering.

He resumed: "The love of one damned."

This is one of the greatest novels set in the Middle Ages. First published in 1831, it knocks Walter Scott into a cocked hat (or, to be more 15C, a chaperon). Yes, it shares some of his limitations in terms of the research resources available in early 19C, and in its Romantic sensibility, but, unlike Scott's works, it gives a clear sense of the 'otherness' of the mediæval world, the sensibility of its people: the protagonists are not contemporary people in fancy dress.

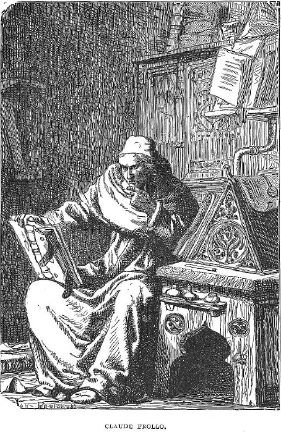

Forget adaptations called The Hunchback of Notre Dame: Hugo did not approve that re-titling of the novel in English-language popular editions, which seems to have begun with Frederic Shoberl's 1833 translation (Bentley, London; Bell & Bradfute, Edinburgh), to appeal to tastes more Gothick than Gothic. Apart from the cathedral itself, the dominant presence is not Quasimodo (a supporting character), but the young Archdeacon of Josas, Claude Frollo – one of the great tragic heroes of Romantic literature, a proto-Dostoevskian, passion-tormented, self-destructive intellectual. One of the disastrous results of Hollywood censorship and self-censorship (the NAMPI and Hays Codes, and Disney 'family values') has been the secularisation or splitting of his character in films. The tragedy of compulsory clerical celibacy is at the core of the novel: if Claude is depicted as a secular figure, the seriousness of his plight is diminished. And only French adaptations – Delannoy's 1956 film, the Roland Petit ballet, the Plamondon/Cocciante musical – seem to remember he is a romantic lead, not a melodrama villain.

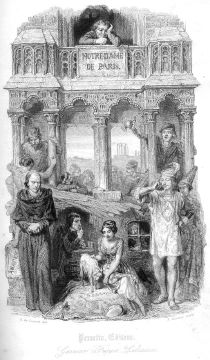

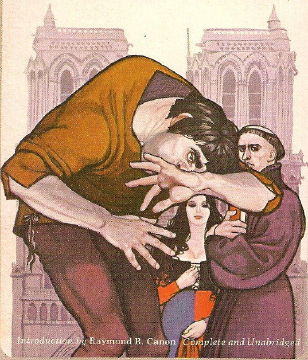

I first read the novel in 1981. I was 16, intending to study mediæval history at university. I discovered the works of François Villon, poet of the 15C Parisian underworld, which led me to Notre Dame de Paris. I got a cheap, US-printed paperback from a station bookstall. (It claimed to be "Complete and Unabridged", but I later discovered that it had been bowdlerised in places!) The cover was dominated by the ungainly Quasimodo, but my eye was caught by the Archdeacon (looking as intense and striking as he should), and I wished he'd move his elbow! Later, I acquired genuinely unabridged editions, English and French, with more delightful illustrations. This Perrotin edition has some beautiful plates, especially the frontispiece by Aimé de Lemud, and I adore the Hetzel edition illustrated by Gustave Brion. Here's a fine English translation with more fine decorations. (And click on the illustrations reproduced here to enlarge them.)

How could I not love a character described thus:

The first pupil whom the Abbé de Saint Pierre de Val, at the moment of beginning his reading on canon law, always perceived, glued to a pillar of the school Saint-Vendregesile, opposite his rostrum, was Claude Frollo, armed with his horn ink-bottle, biting his pen, scribbling on his threadbare knee, and, in winter, blowing on his fingers. The first auditor whom Messire Miles d'Isliers, doctor in decretals, saw arrive every Monday morning, all breathless, at the opening of the gates of the school of the Chef-Saint-Denis, was Claude Frollo. Thus, at sixteen years of age, the young clerk might have held his own, in mystical theology, against a father of the church; in canonical theology, against a father of the councils; in scholastic theology, against a doctor of Sorbonne.

Theology conquered, he had plunged into decretals. From the Master of Sentences, he had passed to the Capitularies of Charlemagne; and he had devoured in succession, in his appetite for science, decretals upon decretals, those of Theodore, Bishop of Hispalus; those of Bouchard, Bishop of Worms; those of Yves, Bishop of Chartres; next the decretal of Gratian, which succeeded the capitularies of Charlemagne; then the collection of Gregory IX.; then the Epistle of Superspecula, of Honorius III. He rendered clear and familiar to himself that vast and tumultuous period of civil law and canon law in conflict and at strife with each other, in the chaos of the Middle Ages, – a period which Bishop Theodore opens in 618, and which Pope Gregory closes in 1227.

Decretals digested, he flung himself upon medicine, on the liberal arts. He studied the science of herbs, the science of unguents; he became an expert in fevers and in contusions, in sprains and abcesses. Jacques d' Espars would have received him as a physician; Richard Hellain, as a surgeon. He also passed through all the degrees of licentiate, master, and doctor of arts. He studied the languages, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, a triple sanctuary then very little frequented. His was a veritable fever for acquiring and hoarding, in the matter of science. At the age of eighteen, he had made his way through the four faculties; it seemed to the young man that life had but one sole object: learning.

By the age of thirty-five, when the main action of the novel takes place, he also has his own alchemy laboratory (a fascinating subject in itself, uniting practical experimentation with philosophy and mysticism)!

He is capable of rare goodness, too – bringing up his little brother Jehan, and adopting a severely disabled four-year-old foundling when he himself is no more than nineteen or twenty; devising sign-language to help Quasimodo communicate when he loses his hearing; educating the teenaged Pierre. But all his attention to other people's needs has left him in a situation in which there is no-one to whom he can take his: he's the person everyone assumes can cope. All his life, he's been 'the good boy', the perfect student, the perfect priest. When the emotions and desires which he has been stifling with brutal self-mortification finally break through, he implodes, destroying everyone he loves and tearing his whole world down around him as he descends inexorably to his doom.

It is heart-breaking to see this brilliant, passionate young man driven to crime and madness, and left shattered on the pavement, because the misogynistic, body-hating religion with which he has been indoctrinated forbids him the love he needs. (I recommend Robert Bartlett's documentaries Inside the Mediæval Mind, especially those on religion and sex, to show how well-drawn Claude is as a case-study of this kind.) It's like watching a rare and beautiful animal in a snare, lashing out at everyone who tries to help it, and chewing off its own paw in its torment. And for what? A harmless, pretty airhead, who prefers equally shallow, pretty soldiers. Another Heloïse might have been worth the madness and torment:

Où est la très sage Helloïs,

Pour qui fut chastré et puis moyne

Pierre Esbaillart à Saint-Denis?

Pour son amour ot cest essoyne.François Villon, Ballade des Dames de Temps Jadis

…But Esméralda the street-dancer? If anything, the shallowness of the object of his passion heightens the tragedy of his fall. (Had she agreed to his advances, the tale would still have ended tragically, along the lines of Heinrich Mann's Professor Unrat/Der Blaue Engel: it's amusing to see Pierre take to wearing motley and do balancing tricks with chairs – but for a man like Claude it would be a catastrophe.)

There are other marvellous things in the novel: the detailed, atmospheric descriptions of old Paris, which some readers are inclined to skip, but which are as vital a part of world-building as Tolkien's creations of his fantasy worlds; the Villonesque Cour des Miracles and its denizens. My second-favourite character is the whimsical and loveable Pierre Gringoire – former street-urchin, poet, dramatist, philosopher and goat-fancier. There are many others, including such mediæval types as the penitent prostitute-turned-anchoress, Pâquette 'la Chantefleurie', and the timeless figure of Jehan Frollo, the spoilt, hard-drinking undergraduate, forever cadging money for booze and women from his big brother. (There are some deliciously funny scenes between Jehan and Claude.) The novel is a vividly believable evocation of a vanished world, and is truly unforgettable.

Back to

TOP